Originally published by John McFarland.

The Texas Supreme Court denied the landowners’ motion for rehearing last Friday in Murphy v. Adams, rejecting their claim that Murphy Exploration had breached their oil and gas lease by failing to drill an offset well or pay liquidated damages. The Court was divided 5-4 on the issue when it issued its original opinion, and the court remained divided 5-4 on rehearing, but both the majority and the dissent issued corrected opinions.

Our firm represented the landowners in the case, so I must admit that it is difficult for me to be objective in reporting on this case. I wrote about the case when the Court of Appeals ruled in favor of the landowners, reversing a summary judgment in Murphy’s favor issued by the trial court.

The landowners’ lease contains the following provision:

It is hereby specifically agreed and stipulated that in the event a well is completed as a producer of oil and/or gas on land adjacent and contiguous to the leased premises, and within 467 feet of the premises covered by this lease, that Lessee herein is hereby obligated to, within 120 days after the completion date of the well or wells on the adjacent acreage, as follows:

(1) to commence drilling operations on the leased acreage and thereafter continue the drilling of such off-set well or wells with due diligence to a depth adequate to test the same formation from which the well or wells are producing from on the adjacent acreage; or

(2) pay the Lessor royalties as provided for in this lease as if an equivalent amount of production of oil and/or gas were being obtained from the off-set location on these leased premises as that which is being produced from the adjacent well or wells; or

(3) release an amount of acreage sufficient to constitute a spacing unit equivalent in size to the spacing unit that would be allocated under the lease to such well or wells on the adjacent lands, as to the zones or strata producing in such adjacent well.

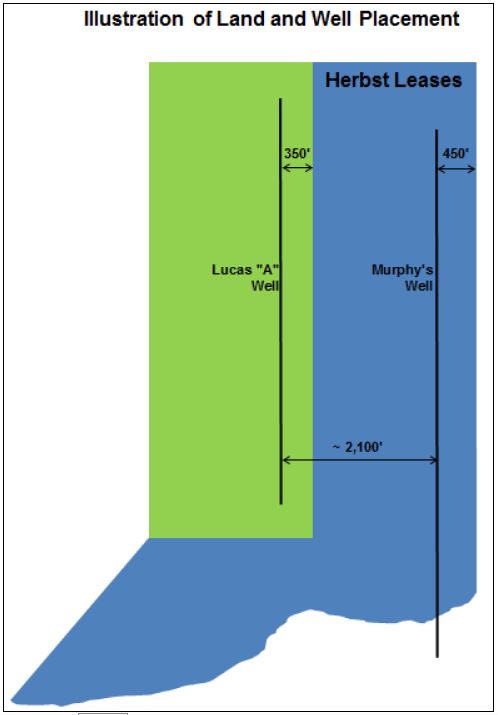

A horizontal well, the Lucas A #H Well, was drilled on a tract adjacent to the plaintiffs’ tract, parallel to and within 467 feet of the leased premises, thus triggering the obligations provided for in the above provision. Murphy drilled a horizontal well on the plaintiffs’ tract, the Herbst Unit B #1H, completed in the same formation as the Lucas well. But the two wells are separated laterally by approximately 2,100 feet. In fact, Murphy drilled its well as far away from the Lucas Well as it could get and still be on the plaintiffs’ lease.

Murphy argued that its well satisfied the offset well provision in the landowners’ lease. Five of the justices on the Supreme Court agreed.

The lease contains no definition of “offset well” and does not say how close such a well must be to the offending well. Most of the arguments in the briefs dealt with the meaning of the term. The landowners argued that an “offset well” is necessarily one that protects against drainage, and that proximity to the draining well is necessary to effectuate that purpose.

Justice Lehrmann, writing for the majority, said that the clause must be construed in light of the “context” of the unconventional nature of the Eagleford formation. “[C]ommentators have recognized that hydrocarbons in ‘the tight reservoirs developed by horizontal drilling … are not susceptible to migration in the same fashion as found in formations traditionally targeted by vertical drilling.’” (quoting from Benjamin Holliday, New Oil and Old Laws: Problems in Allocation of Production to Owners of Non-Participating Royalty Interests in the Era of Horizontal Drilling, 44 St. Mary’s L.J. 771, 813 (2013)). Justice Lehrmann said that the principle that an offset well must be proximate to the draining well “does not apply in the context of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing in the Eagle Ford Shale. … A well may be drilled in close proximity to the lease boundary, yet have absolutely no chance of preventing (or causing) drainage depending on the direction of the horizontal wellbore and the placement of the perforations. … [I]f the parties had intended the offset well to protect against drainage, the provision would presumably have included requirements regarding the direction and placement of the perforated portions of the horizontal wellbore.” Justice Lehrmann concluded from the “context” that there was an “absence of a significant possibility that drainage was in fact occurring.”

Justice Lehrmann then addressed the meaning of “offset well” in the context of horizontal drilling. She quoted the definition of “offset” in Websters Third International Dictionary: something that “serves to counterbalance or to compensate for” something else. She concluded that Murphy’s well serves that purpose. The clause was intended only to “require accelerated drilling when production from a well on an adjacent tract evidenced that the leased tract was also capable of production,” not to protect the lease from drainage.

Justice Lehrmann recognized that the clause might be construed to require protection against drainage in other “contexts”:

[W]e recognize that leases executed in other settings–not involving shale plays and hydraulic fracturing from horizontal wellbores–may utilize similar provisions that remain silent as to proximity requirements. But … we must account for the circumstances in which these leases were executed. Therefore, we limit our holding to the circumstances at hand, which involve unconventional production in tight shale formations. We express no opinion as to the proper interpretation of similar clauses outside this context.

In an amicus brief in support of the landowners’ motion for rehearing, amici pointed out that the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “offset well” as “an oil well drilled opposite another well on an adjoining property.” Landowners referred the court to definitions of offset well that require proximity: “a well drilled on the next location” (Langenkamp, Handbook of Oil Industry Terms & Phrases); a well “next to another owner’s tract on which there is a producing well” (A Dictionary of Petroleum Terms); A “well drilled on one tract of land to prevent the drainage of oil or gas to an adjoining tract of land, on which a well is being drilled or is already in production” (Williams & Meyers, Oil and Gas Law, Manual of Oil & Gas Terms). Justice Johnson’s dissenting opinion also cites several definitions of “offset well”, e.g., “[a]n oil well dug for the specific purpose of preventing drainage of oil to adjoining property” (Ballentine’s Law Dictionary).

Justice Lehrmann’s opinion cited an article by Jason Newman and Louis E. Layrisson, III, Offset Clauses in a World Without Drainage, 9 Tex. J. Oil Gas & Energy L. 1 (2013-2014) in support of her “context” discussion. This article was written by the attorneys representing Murphy, while the case was pending, a fact pointed out to the court by the landowners and amici in briefs on the motion for rehearing. The majority’s corrected opinion eliminates any reference to Newman’s article.

Lesson for landowners: In any lease clause expressly requiring offset wells, define an offset well.

The opinion may also have important broader implications for future oil and gas cases. As pointed out by amici:

Amici are concerned that the Court’s ruling has used the surrounding circumstances doctrine as a pretext for a policy-based balancing of correlative rights. While the balancing of efficient oil and gas development against private property rights may be a legitimate policy goal of this Court in cases regarding certain common law remedies, private contracts are another matter. Texas courts have consistently refused to modify the plain language of oil and gas leases, even when the results are arguably inconsistent with efficient, economic development. Texas courts have recognized that parties to private contracts are masters of their own agreements, and it is not for any court to decide what the parties should have negotiated.

Additionally, this Court’s policy-based decision ignores the purpose of private contracts. While the Court’s ruling states that there is an “absence of a significant possibility that drainage was in fact occurring”, the Lucas Well may actually be draining oil and gas from the Respondents’ property. There is no evidence in the record either way, and for good reason. The Offset Clause in the Leases is a negotiated hedge, a method of avoiding debates about geology, formation characteristics, or whether any individual well is draining Respondents’ tract. Private parties regularly use contracts to allocate risk and provide for protection from even unlikely scenarios in a variety of situations. The mere fact that drainage is possible, no matter how remote, supplies more than enough justification for Respondents’ inclusion and interpretation of the Offset Clause, if justification is needed for the enforcement of freely negotiated contractual terms.

The Court’s reliance on the surrounding circumstances doctrine is troublesome to Amici because it casts uncertainty upon almost every term and provision in every oil and gas lease. Attorneys will no longer be able to reasonably advise their clients as to the legal effect of long-understood terms and provisions when each term and provision can be transformed based on whatever future “context” is expedient to the operator. This Court should grant Respondents’ motion for rehearing in order to reaffirm the limitations imposed by this Court’s previous rulings on the surrounding circumstances doctrine.

In his dissent, Justice Johnson agrees:

The Court acknowledges the rule that evidence of the circumstances surrounding a contract’s execution cannot be used to “add to, alter, or contradict the contract’s text.” … But in concluding that the parties could not have intended the traditional definition of offset well in light of the surrounding circumstances, the Court uses such evidence to alter the well-established meaning of the term.

Curated by Texas Bar Today. Follow us on Twitter @texasbartoday.

from Texas Bar Today https://ift.tt/2Qc9NWE

via Abogado Aly Website

No comments:

Post a Comment